NEED TO KNOW

-

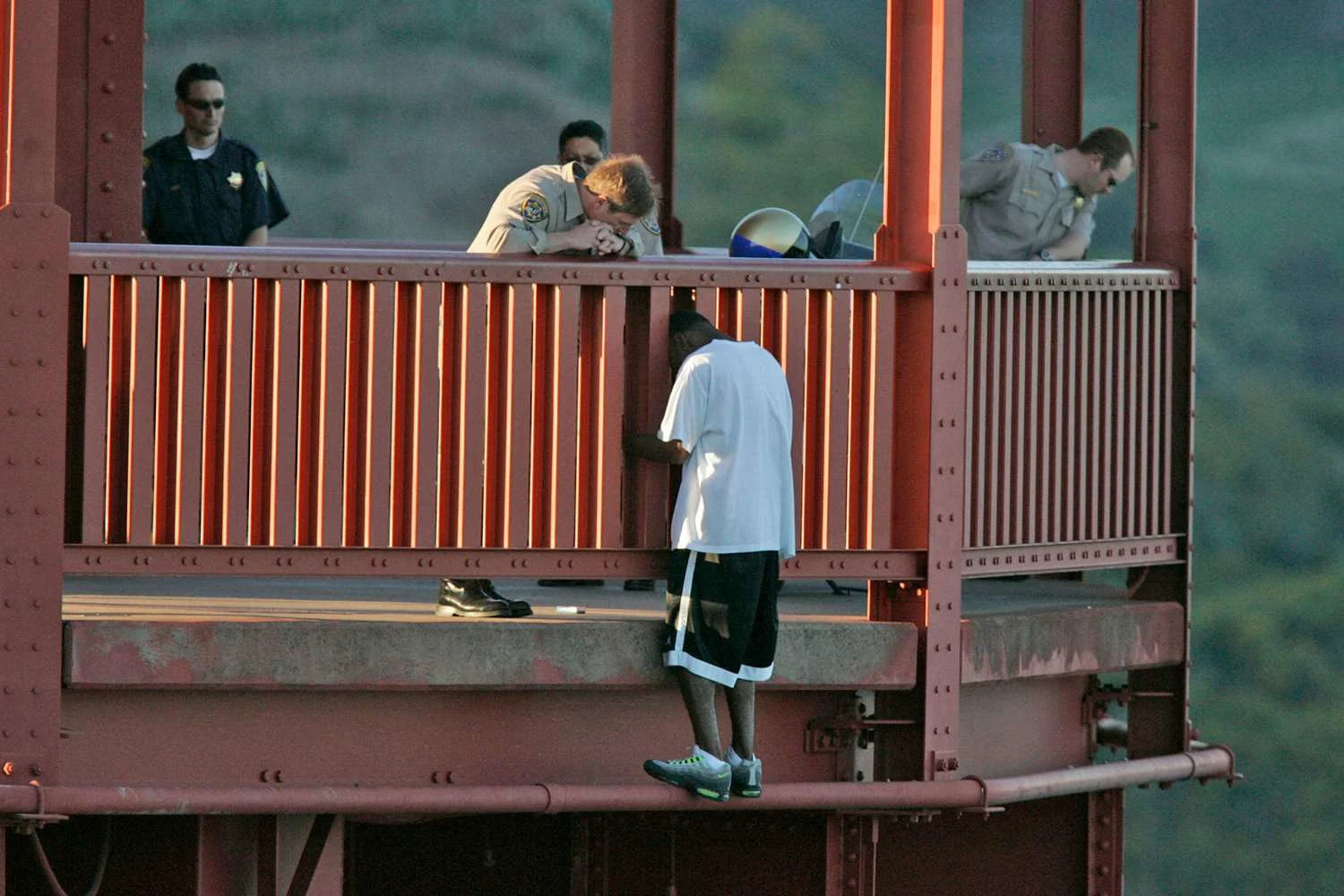

Retired California Highway Patrol Sgt. Kevin Briggs first met Kevin Berthia in March 2005 when Berthia was moments away from jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge

-

Briggs was responsible for talking more than 200 people out of leaping from the famed California landmark

-

After helping Berthia, they later forged a deep friendship and now travel the country speaking about mental health and their work preventing suicide

On the worst morning of his life, Kevin Berthia awoke and, after years of fighting with depression, decided that he was going to drive to the Golden Gate Bridge and jump.

Berthia, who was 22 years old at the time and living in Oakland, Calif., had never been to the famed landmark before and had to repeatedly ask for directions along the way.

But minutes after parking in a lot at the north end of the bridge in March 2005, he left his keys in the ignition and took off walking along the 1.7-mile-long expanse, glancing down at the San Francisco Bay, telling himself, “The water is my freedom. I’m ready to jump.”

Before long, the young man who had just lost his job and was overwhelmed by medical bills after the recent premature birth of his daughter scrambled over the railing and soon found himself balancing on a tiny metal conduit that ran along the outside of the bridge.

The frigid water of the bay churned 220 feet below him.

“I started my countdown,” Berthia recalls now. “And I braced myself for impact.”

Then something unexpected happened. Two decades later, Berthia still refers to it as “a miracle.”

California Highway Patrol Sgt. Kevin Briggs — whose duties involved patrolling the bridge — happened to be passing by when he spotted Berthia on the other side of the railing, lost in thought as he clutched the metal structure.

During his career, Briggs managed to prevent more than 200 people just like Berthia from leaping to their deaths from bridge. He was nicknamed “the guardian of the Golden Gate Bridge.”

When he saw Berthia he calmly swung into action.

“Hi,” Briggs remembers telling Berthia, who was staring intently down into the water. “Is it okay if I come over and speak with you for a while? I’m not going to touch you. I’m just here to talk with you and to listen.”

Over the course of the next 92 minutes, Briggs got Berthia to open up about why he wanted to end his life.

“I never try to tell anyone what to do,” Briggs says. “I just listen with empathy and understanding, let them speak their peace, then get them to think about coming back over the rail.”

It worked.

Berthia admits that for the first time in his life, talking with Briggs, he shared his “deepest, darkest secrets” during their conversation. He pulled himself back over the railing and was soon taken to a local hospital where he spent the next 11 days.

After returning home, Berthia’s mental health problems quickly returned. Seeing a photo of him on the side of the bridge published on the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle only made matters worse.

“For the next eight years,” he says, “I went back into one of the deepest, darkest depressions I’ve ever experienced.”

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE’s free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer, from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

But things began to change in 2013 when the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention reached out to Briggs, who was on the verge of retiring after 23 years with the state highway patrol.

The organization wanted to honor the veteran patrolman for his service and was hoping to get one of the individuals he’d stopped from jumping to present his award at a ceremony in New York City.

Briggs, who had declined the honor on three earlier occasions, was informed by his commander that this time he needed to accept their invitation.

The only problem was that he had never been in contact with any of the individuals whose lives he’d helped save. The closest he ever got to a “thank you” was from Berthia’s mother, Narvella, who wrote him a letter.

“I never followed up with anyone because I never wanted to be a trigger,” Briggs says, acknowledging that he understands why none of the bridge survivors had ever reached out, either: “They want to forget that day. They want to put it behind them.”

One afternoon, Briggs drove to the return address that Berthia’s mom had written on the envelope, introduced himself and told her about the upcoming ceremony.

Narvella quickly hatched a plan to get her son — who by then had attempted to take his life a dozen more times — to New York for the event, telling him he’d won an expense-paid trip to the city from a radio station.

Once Berthia arrived and finally met the man who had saved his life, he was floored.

“I was like, ‘Dang, this whole time it was a cop who saved me,’ ” says Berthia, who was so consumed by the dark thoughts unfolding inside his head on that day in 2005 that he never once looked up to see who it was he was talking to on the side of the bridge. “Being a Black man from Oakland, I’d never had any great run-ins with law enforcement. If I’d known who he was, I never would have opened up to him like I did.”

Within moments of meeting him, Berthia realized none of that mattered.

“We’ve been friends ever since,” says the 62-year-old Briggs, a survivor of cancer and childhood sexual abuse. Berthia insists that their relationship is deeper than that.

“We’re more like brothers,” he says. “What happened that day had nothing to do with him being a White man and me being Black. It’s all about the power of connection, human connection.”

Their reunion proved life changing for Berthia, who gave an off-the-cuff speech while presenting Briggs with his award that floored the hundreds of people in attendance.

“I talked about everything that led me to the bridge that day,” he says. “For the first time in my life I was myself, the person that I’d always wanted to be. I was open and honest and vulnerable. And after I got done, the whole room stood up.”

The crowd’s reaction forced Berthia to realize for the first time in his life that he wasn’t alone in his struggles with suicide and, suddenly, he wanted to do whatever he could to try and change things.

In the years that followed, he not only found the tools he needed better handle his depression but he also created an eponymous foundation that is focused on removing the stigma from mental illness and treatment. A

“Never in a million years did I think that my living in this dark place could help others,” says Berthia, now 42. He has given presentations to thousands of people, ranging from police academy graduates to elementary school pupils.

Numerous times a year he pairs up with Briggs — who has also become a polished, powerful speaker on the issue of suicide prevention — to share their gripping story.

Their hope is to empower others to do what Briggs did on that fateful day 20 years ago, when the two men first crossed paths on the Golden Gate Bridge. Suicide remains prevalent: More than 49,000 people killed themselves in 2023, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“It really is all about just listening and not feeding these folks [in crisis] a bunch of crap, telling them they’re going to be fine,” Briggs says. “It’s about learning how to talk to someone who is suffering.”

The goal, both men say, is to help those in the midst of crisis to understand that they’re not alone.

“It’s a crappy subject,” says Briggs, “but we have a great time.”

Adds Berthia: “It’s not an easy topic to talk about, but as I always tell people, ‘Kevin makes you think, and I make you feel.’ ”

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), text “STRENGTH” to the Crisis Text Line at 741-741 or go to suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

Read the original article on People

Yahoo News – Latest News & Headlines

Read the full article .